How Stories and Predictions Lead Investors Astray

{ Euclidean Q2 2015 Letter }

Many people we know have started businesses or serve as executives in larger enterprises. It is interesting to observe that these individuals often do not apply the principles that have made them successful in business to their personal investment activities.

To be fair, some of them do follow investment programs that we would call very wise, from buying stocks at low prices, to acquiring small businesses at cheap multiples, augmented with a sense that they can increase the businesses’ profitability over time. But these examples tend to be exceptions to the rule.

Far more often, we see people paying inflated prices for securities and taking risks with their personal investments that they would unlikely accept when allocating capital within their businesses. Why is this?

Investment is most intelligent when it is most businesslike. It is amazing to see how many capable businessmen try to operate in Wall Street with complete disregard of all the sound principles through which they have gained success in their own undertakings.

Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor, 1949

When it comes to publically traded securities, investors are easily distracted from the business fundamentals that truly matter because there is so much emotional feeling and story-telling that surrounds the companies those securities represent. Investors naturally develop opinions about specific products, high-profile CEOs, and the role a particular company plays in the world. They often try to find meaning in the narratives about companies that are spread in the financial news and reflected in share price fluctuations.

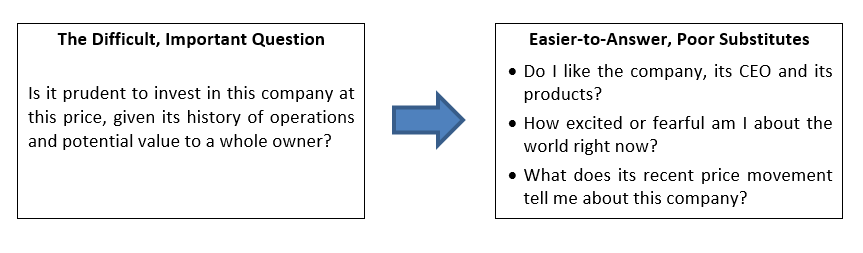

This attention proves misplaced when investors focus on the wrong things and ask the wrong questions. Investors who get distracted by stories and predictions often unwittingly substitute essential questions with others that are easier to answer.

When an investor is influenced by answers to the questions on the right, his decisions lose their connection to a company’s underlying financials and market value. This can cause an investor to buy or sell at prices that are detached from a proper foundation. Just as bad, answers to these kinds of substitute questions tend to have highly fickle answers. A press release, a CNBC “Exclusive”, or a central bank announcement can cause an investor to feel different today about the story they were holding on to just the day before.

Our view is that these kinds of stories are dangerous distractions and should be ignored. We are not suggesting there is never accurate information in stories about a company; rather, we suggest that the stories that matter most, reflect truths that can be found in a company’s financial statements.

Nucor – A Company with a Great Story

Five years ago, a friend in the steel business invited us to a tour of a Nucor Mill in South Carolina. This is something everyone should experience. Even though this was a “mini mill” and only a fraction the size of the integrated steel mills that had once dominated the industry, the scale of the operation was breathtaking. The production line was perhaps a half-mile long and the fire and brimstone involved was something we will never forget.

The centerpiece of the production was a massive electric arc furnace. With blinding sparks and deafening roars, the furnace melts over a hundred tons of scrap metal in about 30 minutes. Then the molten steel is carried in massive cauldrons through the air to where it is poured down the casting line. The steel rushes down like a river of flaming lava and leaves behind the smell of burning metal. In no time, that steel ends up in beautiful round 20-ton coils to be shipped off for a variety of manufacturing uses.

The Nucor story is interesting. By pioneering the mini mill, they were able to build individual mills for 90% less than what it had taken to construct the prior generation’s integrated mills with their blast furnaces. This gave Nucor an enduring, lower fixed-cost advantage over the industry’s larger incumbents. Moreover, Nucor’s pioneering reliance on scrap metal instead of iron ore allowed them to build individual mills near efficient pools of labor and closer to the industries they expected to serve.

Another big part of Nucor’s story is the partnership they fostered with their employees. Nucor tied two-thirds of workers’ pay to the throughput of the mills, the quality of the steel produced, and the safety of their operations. This enabled Nucor to achieve something that many had previously thought impossible: they increased the flexibility and productivity of their operations while their workers made more money than the unionized workers at Nucor’s legacy competitors.

This fact became apparent to us when we chatted with a few Nucor employees in the control room. They believed in Nucor and the opportunity they had to make a difference. They talked about how they made more money than their friends who had union jobs. One began talking about how he could earn extra bonuses by sharing ideas that could increase the plant’s return on assets. “Wow,” we thought, “Nucor’s line employees talk about return on assets!” What’s more, they loved their jobs even though two thirds of their pay was tied to the company’s success and was thus at risk.

It was impossible not to be impressed by the Nucor story. But, from an investing standpoint, was it important to know this story?

Seeing the Stories that Matter in Companies’ Historical Financials

Everyone loves a good story. And business people love a good business story. The strength of a company’s management team, competitive position, and future prospects are all topics that people enjoy hearing about and debating.

Yet, our perspective is that the extent to which these stories and qualitative discussions are meaningful, they can be directly observed in a company’s financial results. Take a great management team, as an example. If a management team is really great, then its greatness must show itself in the form of unusually good financial results. If it doesn’t, then just how great can that management team be? On the other hand, if a company shows consistently high returns on capital, then that could be a sign of great management or the reflection of an enduring moat. Our point is, if an investor says a company is strong in some way then those strengths must show up in strong financial results. Otherwise, the story means nothing.

So, let’s turn back to Nucor. There is plenty of evidence in Nucor’s financials that there is something special about the company. It has a much more favorable financial fingerprint than the prior generation of steel makers. As you can see in the high-level metrics below, Nucor has demonstrated greater profitability, higher returns on equity, and more stable operations than US Steel [1].

Touring a Nucor mill or becoming familiar with the Nucor story is clearly not a prerequisite for appreciating the relative strength of its business. The reasons why mini mills and flexible, performance-based employee relations have been meaningful over time is that they enabled Nucor to deliver better financial results than its competitors. If these superior results had been missing, then any investment decision based on the “Nucor Story” would have been built on sand.

Story-Based Investing – Too Much Prediction and Too Little Price

Colorful stories about a company’s past or present can pull investors’ eyes away from what really matters. But an elaborate prediction of how a company will evolve is even more alluring. After all, it is not a company’s past but its future performance that will determine its value. And, of course, the future path of interest rates, competitors’ actions, and technology adoption may impact the trajectory of a company’s share price.

Unfortunately, while it’s easy to make predictions, it’s not so easy to make predictions that come true. The forecasts of market “gurus” are accurate less than half the time [2], and analysts show a strong tendency to predict that recent trends will continue into the future [3]. Even company CFOs show an astonishing inability to predict where the market will be 12 months from now [4]. Seeking stories about the future may satisfy some deep human need, but it does not make for sound investing.

For these reasons, Euclidean bases its investment process on what is known, while avoiding the temptation to embrace stories about the unknowable. Moreover, our investment process attempts to prepare for an unknowable future by purchasing historically sound companies at low prices such that negative future scenarios are already reflected in their valuations.

This brings us to our final problem with the stories investors tell themselves: they often have no reference to price. This matters because even when a company has demonstrated strong financial performance, it doesn’t always follow that it would have been a good investment.

Take Nucor’s great story as an example. If you had bought Nucor shares during 2007–2008, you would still be underwater in your investment today. Back then, steel prices were high while scrap metal and iron ore were cheap. As a result, Nucor and the rest of the steel industry generated record profits. Investors, as they extrapolated those developments and held onto rosy stories about the future, bid up Nucor’s shares to levels that made them a bad investment. Conversely, the more profitable times to invest in Nucor seem to have been when pessimistic stories swirled around the company, making its shares available at prices lower in relation to the company’s sales and long-term average earnings.

*****

Investors can be easily distracted from what matters most when evaluating public companies as possible investments—namely, the strength of their businesses and their market prices. We believe investors’ habits of latching onto stories and making predictions is a major reason why share prices often fluctuate more rapidly than the underlying, inherent worth of the companies those shares represent [5]. This divergence creates opportunities for long-term investors.

Euclidean pursues these opportunities by overseeing a systematic process that reflects our conviction that making investment decisions based on evidence and conservative prices will do better than those that rely on stories and predictions. We value the privilege of adhering to this process on your behalf and we look forward to connecting with you in person during the second half of the year. Please call us at any time.

Best Regards,

John & Mike

[1] Nucor’s advantages have been evident for some time. US Steel’s management is finally making a focused effort to learn from the Nucor example and evolve its business model to better compete.

[2] CXO Advisory - Guru Grades

[3] To explore some of the data regarding the futility of forecasting, please check out the following resources: David Dreman – Contrarian Investment Strategies; James Montier – The Seven Sins Of Fund Management; Phillip Tetlock – Expert Political Judgment How Good Is It? How Can We Know?

[4] Fuqua School of Business - Research: Corporate Executives Hugely Overconfident

[5] Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends? Robert J Shiller

We share these numbers because they are easy-to-communicate measures that show the results of our systematic process for buying shares in historically sound companies when their earnings are on sale. [6] [7]

It is important to note that Euclidean uses similar concepts but different measures to assess individual companies as potential investments. Our models look at certain metrics over longer periods and seek to understand their volatility and rate of growth. Our process also makes a series of adjustments to company financial statements that our research has found to more accurately assess results, makes complex trade-offs between measures, and so on. These numbers should, however, give you a sense of what you own as a Euclidean Investor. In general, higher numbers for these measures are more attractive. The key measures are:

1) Earnings Yield – This measures how inexpensive a company is in relation to its demonstrated ability to generate cash for its owners. A company with twice the earnings yield as another is half as expensive; therefore, all else being equal, we seek companies with very high Earnings Yields. Earnings Yield reflects a company’s past four-year average earnings before interest and tax, divided by its current enterprise value (enterprise value = market value + debt – cash).

2) Return on Capital – This measures how well a company has historically generated cash for its owners in relation to how much capital has been invested (equity and long-term debt) in the business. At its highest level, this measure reflects two important things. First, it is an indicator of whether a company’s business is efficient at deploying capital in a way that generates additional income for its shareholders. Second, it indicates whether management has good discipline in deciding what to do with the cash it generates. For example, all else being equal, companies that overpay for acquisitions, or retain more capital than they can productively deploy, will show lower returns on capital than businesses that do the opposite. Return on Capital reflects a company’s four-year average earnings before interest and tax, divided by its current equity + long-term debt.

3) Equity / Assets – This measures how much of a company’s assets can be claimed by its common shareholders versus being claimed by others. High numbers here imply that the company owns a large portion of its figurative “house” and, all else being equal, indicates a better readiness to weather tough times.

4) Revenue Growth Rate – This is the annualized rate a company has grown over the past four years.

[6] All Euclidean measures are formed by summing the values of Euclidean’s pro-rata share of each portfolio company’s financials. That is, if Euclidean owns 1% of a company’s shares, it first calculates 1% of that company’s market value, revenue, debt, assets, earnings, and so on. Then, it sums those numbers with its pro-rata share of all other portfolio companies. This provides the total revenue, assets, earnings, etc. across the portfolio that are used to calculate the portfolio’s aggregate measures presented here.

[7] The S&P 500 measures are calculated in a similar way as described above. The market values, revenue, debt, assets, earnings, etc., for each company in the S&P 500 are added together. Those aggregate numbers are then used to calculate the metrics above. For example, the earnings yield of the S&P 500 is calculated as the total average four-year earnings before interest and taxes across all 500 companies divided by those companies’ collective enterprise values (all 500 companies’ market values + cash – debt).

Euclidean’s Largest Holdings as of JUNE 30, 2015

We provide this information because many of you have expressed an interest in talking through individual positions as a means of better understanding how our investment process seeks value.

We are available to discuss these holdings with you at your convenience. We are happy to explain both why our models have found these companies to be attractive as well as our sense of why the market has been pessimistic about their future prospects.

Euclidean’s Ten largest positions as of June 30, 2015 (in alphabetical order)

- Ensign Group – ENSG

- Finish Line – FINL

- Geospace Technologies – GEOS

- Insight Enterprises – NSIT

- Key Tronic Corp – KTCC

- Newpark Resources – NR

- Stepan Company – SCL

- Steve Madden – SHOO

- Sturm Ruger & Co – RGR

- Western Refining – WNR